Saturday 7 June 2008

exam summary

Unfortunately, the coastal zone we have come to rely on is under threat, some of these threats being natural and others being generated by man, these threats can be seen below

· Fishing practices (dredging and trawling damages the seabed)

· Over fishing (leading to the diminishing levels of fish in the ocean)

· Ocean acidification

· Coastal land reclamation

· Shipping industry (oil spills and invasive species etc)

· Aggregate dredging (affects currents and coastal erosion)

· Offshore resource development (oil and gas)

· Aquaculture (spreads disease and destroy coastlines)

· Tourism industry (leads to litter etc)

· Climate change (increased storms etc)

· Sea level rise (increased erosion and change in coastal topography)

There are many governmental, scientific and public organisations which are involved in the management of these pressures and threats, a few examples of these can be seen below

· Governmental organisations (DEFRA)

· Non governmental organisations (National trust, Cornwall wildlife trust)

· Stakeholders

· Scientific companies

· Multi national organisations (UN, IPCC)

· Environmental groups

· The fishing industry

· The tourism industry

· The public

In many cases the management of an issue can be achieved in many ways, the Devon maritime forum aims to provide an overview of coastal issues in Devon and hopes to form greater understanding amongst authorities and agencies involved in the planning and management of the coastal zone, the forum covers a lot of factors concerning the coastal zone however one area of particular area of interest is the problems concerning Lyme bay. Lyme bay contains protected species of sea pink fan, this is under threat from the scallop dredging which is also taking place in the area, the area clearly needs management, the successful implementation of this can be done in a variety of ways

· Create coastal user groups

· Obtain sufficient NGO support for the area

· Create a grass roots system of management

· Involve the community for participation and support

· Build a good scientific base of knowledge about impacts etc

· Conservation zones

· Improve awareness and understanding in the area

Monday 12 May 2008

Introduction to CZM

Coastal zone management is emerging as the hot topic in today's environmental news, threats of climate change and species endangerment have called upon CZM for answers. This blog contains a brief summary of some of the important case studies, topics and legislations regarding coastal zone management, as well as giving me the opportunity to expand my knowledge about current news and events regarding CZM I hope that it will provide others with a baseline of knowledge surrounding the covered topics.

BAP’s: A brief summary

A Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP) is an internationally recognized program which addresses threatened species and habitats and is designed to protect and restore biological systems

The convention of Biological diversity was signed In June 1992by 159 governments at the Earth Summit, which took place in Rio de Janeiro (it is also known as the Rio Convention.). This entered into force on 29 December 1993 and it was the first treaty to provide a legal framework for biodiversity conservation, It called for the creation and enforcement of national strategies and action plans to conserve, protect and enhance biological diversity.

In 1993, following on from the Rio convention, the UK government consulted over three hundred organisations throughout the UK and held a two day seminar to debate the key issues raised at the Convention. The product of this was the launch of Biodiversity: the UK action plan in 1994 which outlined the UK Biodiversity Action Plan for dealing with biodiversity conservation in response to the Rio Convention.

The principal elements of a BAP typically include:

1)Preparing inventories of biological information for selected species or habitats.

2)Assessing the Conservation status of species within specified ecosystems

3)A creation of targets for conservation and restoration

4)Establishing budgets, timelines and institutional partnerships for implementing the BAP.

The United Kingdom biodiversity action plan covers not only Terrestrial species associated with lands within the UK, but also marine species and Migratory birds, which spend a limited time in the UK or its offshore waters. The UK plan encompasses 391 Species Action Plans, 45 Habitat Action Plans and 162 Local Biodiversity Action Plans with targeted actions.

For more information about BAP’s click here

Mullion harbour shoreline management plan

The National Trust acquired Mullion in 1945 principally through a gift from Mr A Meyer. In addition to the harbour itself, the Trust also cares for other buildings within the vicinity of the harbour. The harbour still supports a small fishing community, with a few boats landing mainly crabs, lobster and crawfish. It is now for recreation and quiet enjoyment that most people visit the cove.

Global warming and sea level rise are affecting coastal areas throughout Britain, leaving existing sea defences struggling to provide the same level of protection as in the past. Predictions are that these pressures will continue to increase. Recognising this threat, the Trust commissioned the Mullion Harbour Study in 2004 to identify future options for the long-term management of the harbour. The study looked into the structure of the harbour walls, and assessed the cultural and economic impact of the harbour on the surrounding community. The Trust hopes that the study will assist other harbour owners, as climate change and sea level rise are not faced by the Trust alone.

The Mullion Harbour Study identified a number of possible options for future management:

1. Installation of an offshore breakwater

2. Maintain and repair

3. Managed retreat

Option 1 was rejected as impractical, expensive and environmentally damaging. It was recommended that the Trust adopt a strategy, which combined the other two options. This will allow residents and visitors to enjoy the harbour for as long as possible, but recognises that, at an unpredictable date in the near or distant future, the cove will revert back to its original state of an undeveloped bay.

After Easter 2006, a programme of works costing over £150,000 started to repair the harbour from winter damage and the Trust still continue a structured inspection and maintenance programme, at an estimated cost of at least £5,000 each year however, Once maintenance and repair is no longer deemed viable, the managed retreat phase will begin. In this phase, regular maintenance of the breakwaters will cease and the Trust will systematically remove the breakwaters whilst consolidating the inner harbour walls.

To view the full National Trust Mullion harbour study (2004) click here

The Marine Bill: A change in the right direction or just another consultation

The draft Marine Bill published sets out radical plans for a new network of marine conservation zones around Britain’s coast. The aim of the marine bill hopes that the nature reserves around the UK will have clear conservation objectives, to protect habitats and species of national importance, ensuring that some types of fishing, dredging or other forms of development do not damage them.

The draft bill also includes new systems for managing and protecting our coastal and marine waters through:

- A new UK-wide marine planning system, which will enable us to set a clear direction for how we are going to manage our seas and make the best use of marine resources;

- Simpler licensing of marine developments, for example, offshore wind farms; and

- Improved management of marine and inland fisheries.

Under the proposed marine bill, a new Marine Management Organisation, a centre of marine excellence, will be created to regulate development and activity at sea and enforce environmental protection laws. The draft will also allow migratory and freshwater fisheries to benefit from modernised and more flexible powers. These will give the Environment Agency the tools to better manage fisheries for the benefit of anglers and commercial fishers. However, The Marine Conservation Society (MCS) is extremely disappointed that the Queen’s Speech in 2007 only included a commitment to produce a draft Marine Bill, not a full Marine Bill. Melissa Moore, a MCS Senior Policy Officer said “A draft Marine Bill will amount to little more than another consultation, and we have already had two. The Government needs to speed up this process if it is to meet its manifesto commitment for a Marine Act before the next election.” A Marine Bill is urgently needed to deliver a marine planning system that will enable sustainable development of industries such as marine renewables and the designation of Marine Protected Areas. At present less than 0.001 per cent of our seabed is fully protected and there is currently no legislation to govern their protection

For more information on the current Marine Bill campaign click here

LEAP's: We can do anything if we all work together!!

Local environmental action plans (LEAP’s) help to solve environmental issues at a local level in Europe. LEAP’s involve developing a community vision, assessing environmental issues, setting priorities, and identifying the most appropriate strategies for addressing the top problems and implementing actions that achieve real environmental improvements. LEAP’s rely upon meaningful public input for local governmental decision making and provide a forum for bringing together a diverse group of individuals with different interests, values and perspectives. LEAP’s include the following goals:

1) To improve environmental conditions in the community by implementing concrete, cost-effective action strategies.

2) To promote public awareness and responsibility for environmental issues, and to increase public support for action strategies and investments.

3) To strengthen the capacity of both local government and NGOs to manage and implement environmental programs, including their ability to obtain financing from national and international institutions and sponsors.

4) To promote partnerships between citizens, local government officials, NGO representatives, scientists, and business people, and to learn to work together in solving community problems.

5) To identify, assess, and set environmental priorities for action based on community values and scientific data.

6) To produce a LEAP that identifies specific actions for solving problems and promoting the vision of the community.

7) To fulfill national regulatory requirements to prepare EAP’s, as required by national governments in some EU countries. Over the last several years, LEAP’s have been implemented in several EU countries

For case studies and more information about LEAP’s click here

SAC’s and SSSI’s for habitat protection: A Brief summary

Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) are strictly protected sites designated under the EC Habitats Directive. The Directive requires the establishment of a European network of important conservation sites that make a significant contribution to conserving the 189 habitat types and 788 species identified in Annexes 1 and 2 of the Directive. The listed habitat types and species are those which are considered to be most in need of conservation at a larger European level. The UK network of SAC’s is made up of 614 sites covering a total area of over 2,630,000 ha. SAC’s complement Special protection areas and together form a network of protected sites across the EU called “Natura 2000”.

Compared with other designations SAC’s tend to be large, often covering a number of separate but related sites, and sometimes including areas of developed land and unlike many other designations, SAC’s can stretch beyond the low tide mark into the marine environment. In fact, some are almost all completely found within the marine environment.

Sites of special scientific interest (SSSI) were generated under the wildlife and countryside act 1981 which states that the government has a duty to notify as an SSSI any land which in its opinion is of special interest by reason of any of its flora, fauna, geological or physiographical features it may have. SSSI’s in the UK are designated by Natural England however, the SSSI is not necessarily owned by a conservation organisation or by the Government, they can be owned by anybody. The designation is primarily to identify those areas worthy of preservation. The recent Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 has strengthened the law and given greater power to the designating body of a SSSI to enter into management agreements, refuse consent for damaging operations and to take action where damage is being caused through neglect or inappropriate management. Local Authorities and other public institutions now also have a statutory duty to further the conservation and enhancement of SSSI’s.

For a summary of SAC designation and selection click here

For a list of SAC’s in the UK click here

For more information on SSSI’s click here

Sunday 11 May 2008

The Crown Estate and damage by fishing in Lyme Bay and Falmouth

The Crown Estate is one of the UK's largest property owners and has control and ownership over the seabed. However, in a recent paper published by Tom Appleby of Bristol University's School of Law it has been reported that the crown estate may not be looking after the biodiversity of the seabed. His report examines a dispute between local fisherman and environmentalists on the management of Lyme Bay, an area of the English Channel owned by the Crown Estate.

His research focuses on the competing rights of commercial scallop dredgers fishing in Lyme Bay. Scallop dredgers use a technique that involves dragging steel bags with sprung-loaded teeth across the seabed, and research suggests that this dredging technique has damaged the reef situated within Lyme Bay, this reef is inhabited by a number of rare marine species including the protected pink sea fan (Eunicella verrucosa). To see a video of a scallop dredger in action click here. At this point in time nearly all fishing in UK waters is permitted, however the Crown Estate’s sea-bed is governed by differing legislations, these include the 2006 Natural Environment and Rural Communities (NERC) bill which states that “all public authorities must, in exercising its functions, have regard, so far as is possible, to the purpose of conserving biodiversity”. In addition to this the area is also part of a UK biodiversity action plan to maintain the reef and the natural life it supports. It is also important to note that under The 1981 Wildlife and Countryside Act it is a criminal offence to damage certain species, included in this bill is the pink sea fan. The research paper highlights the need for clarification in the law as to whether such excessive damage to Crown Estate property can take place as a legitimate activity for those in pursuit of the public right to fish, without causing a wrongful act to the owner of the sea-bed, it also proposes that The Crown Estate should actively manage its marine estate to protect biodiversity and stop harmful fishing practices where necessary to stop such damage.

This case can be compared to a recent ban of Scallop dredging within the Fal estuary where conservationists successfully threatened to take the Government to the European Court for failure to protect marine wildlife. The Fal estuary was designated a special area of conservation (SAC) 12 years ago and a voluntary agreement among fishermen was made which involved dredging for scallops in selected areas of the Fal for two months of the year, this agreement subsequently failed and conservationists accused the Government of allowing the destruction of protected Maerl beds which can take thousands of years to grow. The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) has taken the advice of Natural England and its conservation advisers, and has said it intends to prohibit beam trawling, trawling and scallop dredging permanently from November this year, after which only fishing with hook and line will be permitted. The ban sets an example for delicate habitats in protected areas all around our coastline as this is one of the few times commercial fishing activity has ever been banned for conservation reasons in the sea around Britain's coast. Will the situation at Lyme bay follow the same path?

To view an overview of the Fal estuary’s dredging ban click here.

Evaluative tooling for coastal zone management: EIA’s and SEA’s

An Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is an assessment and analysis of the likely positive and/or negative influences a project or business proposition may have on the environment. EIA’s can be defined as: “The process of identifying, predicting, evaluating and mitigating the biophysical, social, and other associated effects of development proposals before major decisions are taken and commitments made.” The purpose of EIA’s is to ensure that corporations consider environmental impacts before they decide to proceed with new projects. EIA’s predict what and how a specific action can do to the environment.

The EIA directive was first introduced in 1985 and was amended in 1997. The directive was amended again in 2003 following the 1998 signature by the EU of the Aarhus convention on public participation in environmental matters. Under the new EU directive, an EIA must provide certain information to comply. These are some of the key areas that are required:

1. Description of the project

2. Alternatives that have been considered

3. Description of the environment

4. Description of the significant effects on the environment

5. Mitigation

EIA’s are imperative for coastal zone management as they are sometimes all that stands for the protection of the environment and coastal zones

A Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is a system for incorporating environmental considerations into policies, plans and programmes. SEA’s were created because the European Union directive on Environmental Impact Assessments (known as the EIA Directive) only applied to certain projects. This was seen to have many flaws as it only dealt with specific effects on a small-scale local level whereas many environmentally damaging decisions were being made at a more strategic level. The incorporation of SEA’s in Europe began with the convention on environmental impact assessment in a transboundary context (the Espoo convention) introduced SEA’s in 1991. in 2001 the European SEA directive stated that all European union member states should have integrated the directive into their law by July 2004. The SEA Directive aims to introduce a systematic assessment of the environmental effects of strategic land use.

An SEA is conducted before an EIA is undertaken. This allows information on the environmental impact of a plan move down different stages of decision making and can be used in conjunction with an EIA at a later stage. This should reduce the amount of work that needs to be undertaken.

The structure of an SEA is as follows:

1) Screening: this is an investigation to whether the plan or programme falls under the SEA legislation,

2) Scoping: this defines the boundaries of investigation, assessment and assumptions required,

3) Documentation of the state of the environment: effectively a baseline on which to base judgments,

4) Determination of the likely (non-marginal) environmental impacts.

5) Informing and consulting the public.

6) Monitoring of the effects of plans and programmes after their implementation.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) : A breif summary

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is an international agreement that emerged from the third United nations Convention Conference on the Law of the Sea (1973 through 1982). The basic thought behind UNCLOS was to create a set of international legislations that set out the rights and responsibilities of nations concerning their use of the world's oceans, the environment, and the management of marine natural resources . UNCLOS came into force on November the 16th 1994 and replaced the less detailed freedom of the seas concept, which dated back to 17th century, this specified that a nations rights were limited to a belt of water that extended for 3 nautical miles from the coastline, all waters beyond this point were considered international waters and free to all nations.

Upon introduction, UNCLOS introduced a number of new regulations and proposals which included setting limits, navigation, archipelagic status and transit regimes, exclusive economic zones (EEZs), continental shelf jurisdiction, deep seabed mining, the exploitation regime, protection of the marine environment, scientific research, and settlement of marine disputes.

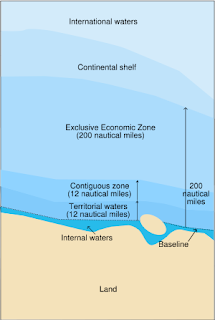

UNCLOS sets a legally binding international standard, which aims to protect the marine wildlife and environment. One of the most important components of the Law of the sea is that it set new limits and regulations for a variety of different areas. These areas can be seen on the image below and are described as follows:

Internal waters: this area Covers all water and waterways on the landward side of the baseline. The coastal state is free to set laws, regulate use, and use any resource. Foreign vessels have no right of passage within internal waters.

Territorial waters: This area stretches Out to 12 nautical miles from the baseline, the coastal state is free to set laws, regulate use, and use any resource. International Vessels are given the right of innocent passage through any territorial waters

Contiguous zone: this area stretches a further 12 or 24 nautical miles from the territorial sea baseline limit and in this zone a state can continue to enforce laws regarding activities such as smuggling or illegal immigration.

Exclusive economic zone: this zone Extends 200 nautical miles from the baseline . Within this area, the coastal nation has sole exploitation rights over all natural resources.

Continental shelf: The continental shelf is defined as the natural prolongation of the land territory to the continental margin's outer edge, or 200 nautical miles from the coastal state’s baseline, whichever is greater. State’s continental shelf may exceed 200 nautical miles until the natural prolongation ends, but it may never exceed 350 nautical miles. States have the right to harvest mineral and non-living material in the subsoil of its continental shelf.

There is currently a large debate about how well the treaty is doing as it proposed, although for member states the treaty protects the environment and valuable resources many feel that it will not fully serve its purpose unless a greater number of influential countries sign up to it. UNCLOS is a fundamental tool to be used and referred to whilst carrying out coastal zone management.

Offshore marine Aggregate Dredging: A major industry or a major hazard.

Marine aggregate dredging is a major industry which supplies raw materials to the UK construction industry, because of this it is of great importance to the countries economy, however the effects of obtaining this valuable resource from the seabed is damaging marine ecosystems, commercial fishing industries and beaches along our coastline.

Marine aggregate dredging is a form of strip mining, sand and gravel is removed from the seabed, the extraction is carried out by large vessels with a capacity of 5000 tonnes or greater by means of suction All offshore marine aggregate dredging in the UK takes place within the 12 nautical mile limit. The material obtained from the seabed is screened for suitability with over half of the material returned to the sea as unsuitable (mud, silt, shells and other unwanted constituents of the seabed)

.Licences to dredge are issued by the UK central government, which administers a licensing system set out in the marine mineral guidance note 1 (MMG1), this licensing procedure requires the applicant to undertake an environmental impact assessment based on the terms within the MMG1. When the appropriate parties have studied this the applicant can then apply to obtain a license from the crown estate (dredging takes place within the 12 mile limit and this comes under the crown estates jurisdiction) who will specify the period of license, volume of extraction and other various requirements.

Both sand and gravel beds support rich and varied biological communities, the nature of these habitats can change depending on location but both sand and gravel areas are important to both fish and other seafloor species. Marine life at the site of extraction experiences a severe rate of mortality, and the rejected constituents of the dredge smother the seabed for great areas around the extraction site. As well as the destruction of marine life, aggregate dredging also changes the morphology of the coastline, during the stormy winter months, sand and shingle are drawn from beaches and into the ocean, in comparison, in calmer weather these materials accumilate and beaches regenerate. Dredging of offshore aggregates can disturb this relationship and this can leave beaches prone to erosion, this process can be seen in Norfolk and on the Gower peninsular

The Aggregate dredging industry is rapidly emerging as an industry of great importance for the UK’s economy, however, we are not evaluating the consequences of this development. There are many things that can be done in the near future to conserve this limited resource and protect marine biodiversity:

· Better Environmental impact assessments and monitoring will enable a more sustainable and environmentally friendly practice to take place

· Less demand for marine based aggregates as a result of the development of the recycled aggregate industry

This will lead to a greater protection of current sea defences, marine communities and marine diversity.

For more information about the methods, legislation and effects of marine aggregate dredging click here

Potential impacts of climate change on the Cambodian coastal zone: A Case Study

The Cambodian coastal zone is located in the southwest part of the country, it covers an area of approximately 18,300km2 and plays a significant role in agriculture, fishery, tourism and sea transport, however this environment that exists in a delicate balance between natural process and human activities is under threat. If climate change and sea level rise induced by global warming progress as predicted the consequences for the low-lying coastal areas could be seriously affected. The coastal zone of Cambodia consists of six protected areas, which cover a total area of about 390,000 ha. These areas form to make a very important coastal zone for Cambodia and its people. In the future coastal zones will be directly and indirectly affected by the impacts of climate change and important decisions about coastal management will need to be made. The main impacts of climate change upon Cambodia’s coastline have been identified as follows:

- Coastal Erosion: caused by removal of coastal vegetation such as mangrove forests, agricultural development and other human activities has left the coastal zone more prone to erosion from sea level rise and increased meteorological events such as tropical cyclones, storms and tidal surges

- Coral reefs: an increase in sea surface temperatures will pose a major threat to the coral reefs surrounding the coastline. The coral reefs are also under great threat from illegal fishing methods and cutting for sale.

At this point in time there is currently no infrastructure to protect the Cambodian coastline, communities that inhabit the coastal area may be at risk from food supply shortages, health issues and other consequences associated with climate change. As to date no study has been done in the field to work out the true nature of the impacts of climate change and for the possible adaptations available. Because of this Cambodia should prepare detailed policies and plans to get an idea of how climate change will affect its coastline. These could include:

· Comprehensive studies to acquire the existing conditions and their trends in relation to climate change

· A comprehensive vulnerability assessment for the coastal zone (could include SWOT analysis)

· A relevant management plan

· An adaptation plan

· Education and public awareness campaign

Saturday 10 May 2008

Likely impacts of climate change on the Cornish coastline and management techniques available to combat it

"The problems of the world cannot possibly be solved by sceptics or cynics whose horizons are limited by the obvious realities. We need men who can dream of things that never were." (John. F Kennedy, 1963).

Climate change has emerged as the single greatest environmental challenge that the human race has ever had to face (Defra, 2008), its threat has been known for decades, however its consequences are only just beginning to develop, this report will discuss the physics behind climate change, its likely impacts on the Cornish coastline and appropriate management techniques that can be implemented to combat its risk.

The earth’s climate is a finely balanced system, which is governed by many factors such as temperature, wind and precipitation, it influences the weather, the way the ocean works and the way in which we live our lives. In the past the earth’s climate has changed radically in response to a number of natural causes, and unfortunately, it is doing so again. Since industrialisation occurred over a century ago, the earth has warmed by 0.74°C, with around 0.4°C of this increase occurring within the last 30 years (Defra, 2008). A report published by IPCC (intergovernmental panel on climate change) named the Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) stated that there was no doubt that the result of human activity is the main contributor to the changes in the earth’s climate (Defra, 2008). Global greenhouse emissions have increased by 70% since pre-industrial times (IPCC, 2007) and the accumulation of these gases (carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide) in the atmosphere has created a greenhouse effect, which warms the planet and exaggerates its climatic conditions. Because of the excessive burning of fossil fuels and an increased amount of deforestation globally over the last century, the concentration of these greenhouse gases has now reached critical levels and increasingly irregular climatic conditions are beginning to become more apparent. The AR4 report predicts that if the levels of carbon emissions within the atmosphere continue to rise, average global temperatures over the next century are likely to rise between 1.1 and 6.4°C, this will result in a predicted rise in global sea level of between 20-60cm, increased melting of glaciers and ice caps and intensified weather conditions (IPCC, 2007). Unfortunately, these global scale problems, can often be overlooked at a local level and without the knowledge of how climate change will affect the locations habitats, ecosystems and economy, nothing can be done to preserve what needs to be protected.

Cornwall is a county surrounded by the ocean. More so than any other county in the United Kingdom, it is highly dependent on its physical characteristics and wildlife, its economy relies almost exclusively on the natural resources that exist within the local environment, these include, Agriculture, mineral extraction and tourism. The future of these resources depends on the natural environmental on which they stand, tourism for example, requires that the physical environment and coastal zones remain in good condition, however this environment is at risk of being changed or even destroyed as a result of climate change, this poses significant and life changing problems for Cornwall’s economy, ecosystems and communities, but also provides valuable opportunities.

the future of Cornwall’s coastline is ever changing, Sea level rise will not only increase the probability of flooding but it will also greatly increase the effects of coastal erosion and saltwater inundation, thus destroying valuable habitats, ecosystems and creating a large change for tourism industry within the area to deal with and recover from. Coastal risk assessment results published by the National trust state that 279 kilometres of national trust land alone in the southwest will be at risk from erosion over the next 100 years (National trust, 2005) and it is not yet known what sort of effect this will have on the coastline and surrounding area. Cornwall is a host to a variety of diverse flora and fauna with a large proportion being found along the coastline, the effects of erosion and saltwater inundation due to sea level rise could destroy habitats and ecosystems that have been present along the coastline for hundreds of years, this may send species elsewhere and away from the Cornish coastline which will reduce the amount of visitors contributing to the Cornish economy. Many of the popular seaside towns that attract thousands of visitors each year are under great risk from the effects of sea level rise, be it from flooding or coastal erosion, because of this, Cornwall’s tourism and economy lie in the balance of successful and sustainable implementation of management techniques used to combat the problems linked to climate change and sea level rise.

The choice and implementation of successful management techniques used to combat sea level rise need to be carefully reviewed and researched before they can be considered for use, each location requires different methods of management and because of this it is important to look at the problems at a local level so that the type of management can be distinguished, all the management methods proposed should aim to meet the three objectives of coastal management, these are to avoid development in areas that are vulnerable to coastal inundation or erosion, ensure that coastal ecosystems and habitats continue to function and most importantly, to protect human lives, essential properties and the regions economy (IPCC, 1990). The techniques required to combat the effects of sea level rise and meet the objectives of coastal management in the southwest fall into three very different categories, retreat, accommodation and protection (IPCC, 1990). For each of these methods to function correctly it is important to keep in mind that one method alone may not be the answer to all the problems at any given location and that the implementation of each of the following management methods must be coupled with a large amount of public education, awareness and participation.

The retreat method of management may be the most extreme and uneconomical method for coastal communities to initiate, it involves little or no effort to protect the land under risk and requires the abandonment of valuable land and structures in areas of high risk, this will inevitably lead to a need for the resettlement of communities away from their original position and can force coastal ecosystems inland, possibly even destroying them (IPCC, 1990). Because of this, the retreat method can sometimes be seen as a last resort as it can change the coastline so much that the region economics, ecosystems and community morale suffer greatly as a result, because of this the retreat method may only be suitable under extreme circumstances of coastal erosion and inundation (IPCC, 1990). This method is currently being implemented by the National trust on the cliffs of Birling gap in Sussex, the cliffs are eroding at such a rate that the trust now believes that it is more sustainable and financially viable to abandon the coastguard cottages situated on the cliff, and allow the coastline to evolve naturally rather than try to create other forms of defence (National trust, 2005).

The protection method of coastal management requires defensive measures to protect the exposed proportion of coastline from saltwater inundation, flooding, wave impact and erosion (IPCC, 1990). It usually involves the construction of hard defensive structures such as breakwaters, floodwalls, groins and seawalls. These structures commonly have excessive build times and are often very expensive to build and maintain. Protection can also come in the form of soft defensive structures such as beach filling, dune building and wetland creation (IPCC, 1990). Unfortunately there is no guideline set for which defence to use in which situation and so each location must be carefully studied and evaluated to reach an educated conclusion. There is also no guarantee that hard defences will work over a long period of time. As sea levels rise and storms increase, it will become more difficult to maintain current defences and build new ones, the defences may even just direct the problem geographically elsewhere along the coast and cause environmental harm by moving the problem to a new, less prepared location, because of this organisations such as the National trust, believe that hard defences are no longer a sustainable and viable answer to the problems concern with coastal change (National trust, 2005).

The accommodation method of coastal management combines the positive attributes from both of the previous methods. It involves the continued use of the land at risk, but requires the evolution of buildings and farming techniques to accommodate for flooding and coastal erosion, this can include, elevating buildings on piles, switching from agriculture to aquaculture or growing salt tolerant crops (IPCC, 1990). This method is most economical and sustainable over a long period of time but can be hard to initiate. Accommodation provides opportunities for inundated land to be used for new purposes, which can improve the economy, an example of this is the use of different farming techniques (such as aquaculture), which would have previously been unavailable or economical before the inundation took place, thus expanding the regions choices for a more sustainable economy (IPCC, 1990). Unfortunately this can also have social implications because changes in farming techniques will no doubt result in major lifestyle changes and changing buildings to accommodate inundation may worsen living conditions which will have an adverse effect on public health (IPCC, 1990).

It seems ironic that the fossil fuels, which aided the growth and progression of the world around us today, are undoubtedly going to force us to change the way we live tomorrow. If climate change is not prevented there is the possibility that economies and communities will fall apart, however there is also the hope that it will bring communities together and allow them to have a greater knowledge about the environment around them hopefully helping them to live their lives in a more sustainable, natural and enjoyable way.